Welcome to Hemlock and Canadice Lakes!

Barns Businesses Cemeteries Churches Clinton & Sullivan Columns Communities Documents Events Time Line Fairs & Festivals Farm & Garden Hiking Homesteads Lake Cottages Lake Scenes Landscapes Library News Articles Old Maps Old Roads & Bridges Organizations People Photo Gallery Podcasts Railroad Reservoir Schools State Forest Veterans Videos

|

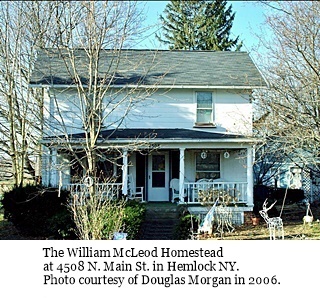

The William McLeod Homestead at 4508 N. Main St. Hemlock NY |

Click any image to enlarge. |

|

The Astronomer’s Home - The William McLeod House at 4508 N. Main Street Hemlock NY

A Historical review by Joy Lewis, the Richmond NY Historian.

1 The William McLeod Homestead at 4508 N. Main St. in Hemlock NY. Photo courtesy of Douglas Morgan in 2006. Norman McLeod was born in Scotland in 1811. He embarked for the Americas in his mid-twenties, settling in Kingston, Ontario, Canada, where he married Margaret McBean just before he turned thirty. Their first three children were born in Kingston: William, Donald, and Elizabeth. Libbie was a baby when they came to Ontario County, New York. Their youngest daughter Isabelle was born in 1856 in Canadice. About ten years after Belle’s arrival the family relocated to Hemlock. The eldest son William was twenty-six in 1867 when he bought two adjoining house lots on Main Street: number 4508 (the north lot) and number 4516 (the south lot). He and his father built a house on the south lot and the family moved in. Donald McLeod, William’s younger brother, bought the lot on the north side of 4508, but very quickly sold it and moved away to Tennessee. The property at 4508 remained unimproved until 1880 when William built a two-story frame house there. It was at about this time that William’s father Norman died and his sister Elizabeth married. William, his widowed mother Margaret, and his spinster sister Belle moved into the new house and the house at 4516 was sold. Right around this time William bought from his neighbor on the the north side of his lot (recently-widowed Mrs. Julia Knowles of 4504) two slender strips of land to enlarge his holding. The carriage barn he built behind his house was so close to Mrs. Knowles’ barn that there was only a very narrow “alley-way” between the two buildings. The driveways of both homes, over the course of many years, spread out until by the middle of the twentieth century they merged. (A survey completed in the 1970s reestablished the boundary between the two properties and the home owners tidied up their drives and the median between them.) William McLeod was a brilliant man, interested in many subjects of study. He was a self-taught engineer and a dedicated amateur astronomer. During the Civil War he’d served in the 104th New York Regiment for nearly two years. He was wounded at Manassas, Virginia, in the summer of 1862 and as a result his left arm was amputated. He returned to the family home in Canadice and it was shortly after the close of the war that the family came to Hemlock. It was about 1876, the first year that the Hemlock Fair was held at its present location on south Main Street, that William McLeod built the grandstand overlooking the race track. He operated the grandstand concession until 1901 when he sold it to the Agricultural Society. With his shirt sleeve pinned up at the shoulder, William McLeod was a familiar figure around the village. His obituary noted that he “maintained an observatory in his barn ... and [was] famed locally for his ability to read the signs of the heavens.” He was an inventor (receiving a patent in 1896 for a folding crate), a businessman, and a concerned citizen. In 1913 he organized a local petition directed to the Committee on Invalid Pensions, an agency of the United States Congress, urging passage of a bill to increase the pension of veterans who had lost an arm or a leg in the Civil War. His mother died in 1897 and his sister Belle almost fifteen years later. William sold his house the next year and moved to Rochester, where he died in 1924. His obituary made note of the fact that ever “since he had been living in Rochester, he made it a point to be here [in Hemlock] for Memorial Day.” Herman Heckman bought the McLeod house in 1914. He and his wife Emma were an older couple, childless. The son of John and Emma (Tice) Heckman, Herman grew up in Easton, Pennsylvania. He went to work for the Lehigh Valley Railroad in 1876 and ten years later was promoted to locomotive engineer. In January 1904 he was assigned the “Rochester Branch” - the train that ran daily from Hemlock to Rochester - a position he held for twenty years. The Heckmans moved from Manchester to Hemlock where they rented a house for some years before purchasing 4508 Main Street. Engineer Heckman was a respected locomotive driver. In all his decades in the cab, only two accidents involving his train have been documented. Both occurred at the West Main Street crossing in Honeoye Falls. On August 30, 1904 - a fine summer’s day - Train 671 left the Hemlock Depot at 3:15 PM, running on time. Heckman was at the throttle of Engine 643, pulling three freight cars, a passenger coach, one combination car, and a baggage car. They arrived in Lima a few minutes behind schedule and left that station at 4:08, thirteen minutes late. As Heckman approached the crossing at Honeoye Falls nine minutes later, he sounded his whistle, but he did not slow the train; he was bent on making up the time. A butcher’s delivery wagon drawn by a single horse neared the crossing as the train came into view. Eyewitness accounts vary as to what happened next, but more than one reported that the horse reared at the sound of the train’s whistle. Others said the driver of the wagon urged the horse forward in an attempt to cross in front of the train. The horse did make it across the tracks safely, but the wagon did not. The train engine struck the rear wheels of the wagon, demolishing it and sending pounds of beef in all directions. Mr. Loren Parsons, the driver of the wagon, was in his early sixties. He was badly mangled by the impact. A special train was organized to take him to the hospital in Rochester, but he died some hours later. His passenger, nine-year-old Charlie Woodard, was thrown clear of the wreck, suffering a broken leg and a severe laceration to the head. He, too, was transported to the hospital in Rochester. Charlie recovered from his injuries and lived another half century. Herman Heckman was again at the controls of a Lehigh Valley train as it sped from Hemlock to Rochester on the afternoon of January 28, 1916. Heckman’s freight train approached the same crossing in Honeoye Falls. A car driven by the Rev. Martin J. Cluney, priest of a local Catholic parish, approached the crossing with the apparent intent to cross the tracks. The train, traveling in excess of the town limit of six miles per hour, did not have time to stop and the automobile was struck broadside. Father Cluney was thrown clear, shaken up and suffering a cut on his head. His passenger, Bruno Pilo the church sexton, was badly injured and died in the hospital a few hours later. There isn’t much else known of Herman and Emma Heckman while they lived in Hemlock. They moved away from the village in 1919 and went to Rochester, and the house was sold to Olin and Gladys Mather. Olin was an enterprising young man in his late twenties, married, and the father of two little girls and a son: Olive was six, Beryl, five, and Grove a babe in arms. They moved in April and in November their fourth child, George, was born. The Mather family had lived for two generations in Dixon Hollow, a little settlement on the eastern border of Livonia along the Canadice Outlet. After the Mather woolen mill burned in 1860, Olin’s grandfather Norman built a large frame building on the same site. This became the headquarters of the Mather sawmill and cooper shop. Norman and his sons produced a great variety of goods, including wet and dry barrels, butter tubs, wooden pails, bathtubs, and clapboards. (Frank Connor, Livonia historian in the early part of the twentieth century, wrote that in 1930 one of the Mather bathtubs was still in existence somewhere in Hemlock. Alas, he did not mention which household possessed the exotic item.) Ever since the creation of the Rochester Waterworks Company three decades earlier, land surrounding Hemlock and Canadice Lakes and their outlet streams had been gradually bought up by the city. In June of 1918 Olin’s widowed mother Phyla sold her acreage in Dixon Hollow to the Rochester Waterworks Company. Within the next two years all of the privately-owned property in the old settlement was sold to the city and the place was deserted. Phyla retained ownership of the mill building and when Olin moved to Hemlock, he moved the mill as well. First he cut it in half, then, one at a time, loaded each half onto log rollers. Cautiously, drawn by horses, each half-a-mill was eased down the hill to the main road, then continued its journey along “the Springwater Road” until it arrived in Hemlock. The two pieces were joined back together and the whole thing set up on the north side of Clay Street, near the corner with Main. Olin restructured the building as a cider mill, which remained in operation for many years (and today houses apartments). The cider business was a profitable one. The Mather family prospered. Under their ownership the house at 4508 Main Street was spruced up, furnished with the accoutrements of their Dixon Hollow home. In one corner was an upright piano - Olin’s coronet rested on top among a flutter of family photographs - flanked by a marble-topped table and a rocking chair. A library table was set in the center of the room, holding a kerosene lamp with a frosted globe. Narrow striped wallpaper covered the living room walls and on the floor was a rose-patterned carpet. On the wooden mantle sat an ornate clock and a pair of commemorative plates. On one side of the fireplace was a dainty folding desk, and on the other side an Eastlake glider chair. Lace curtains over heavy green shades adorned the windows. In his backyard Olin planted an apple orchard. He cultivated blackberries, raspberries, red currants, and at least three varieties of grapes. He planted apricot trees and pear trees in the back yard and flowering snowball bushes bordering the wide front porch. Along the south side of the barn were maple and walnut trees interspersed among elms and hemlocks. The manicured grounds were a lush splendor. Olin died in the spring of 1945 at age sixty, only a few weeks after selling the cider mill. His funeral was conducted from the front room of his home by Rev. Hausser, minister of Hemlock Methodist Church (where the Mather family were faithful members). His children had all married and scattered. For years Olive had lived in Minneapolis with her husband Henry Roome, where she taught school. But in the early forties, ever since Henry had been drafted into the Army, Olive and her infant daughter Louise had been living in Hemlock with her parents. She taught high school history classes at the Hemlock School for a couple years before moving back home to Minnesota after the war. At the time of her father’s death Beryl, married to high school sweetheart Hugh Morrison, lived on Conesus’s East Lake Road where Hugh owned a used car lot. Son Grove was also married; he lived with his wife Florence and her parents in Perinton. George, twenty five, was serving in the U.S. Air Force, stationed in Florida. Gladys lived alone in the house for a year or two. Then Beryl was divorced and came home to live with her mother. The two women remained in the house until 1961 when they moved to Rochester. The house stood empty for about four years before it was bought by James VanDusen; he rented it to the Bill Hoppough family. In 1967 Bill and Bev (Benham) Hoppough bought the house and lived there for more than twenty years.

|

||

|

On A Personal Note I was only weeks away from turning six in the autumn of 1958 when we moved into the house on the north side of the Mather house. My sister Wendy was a year younger and our brother Rob was almost three. Mrs. Mather and her daughter Beryl lived next door to us for the next few years. Mrs. Mather, as I remember her, was a tiny woman with swaths of snow white hair wrapped around her head. She wore long gray dresses. We children were only occasionally invited inside; all I remember of the interior of the house at that time was how dark it was. The green shades in the front room were never raised, as far as we knew, and the primitive kitchen at the back was a closed-in cupboard-like space with only a single window, high up. Though we didn’t go into the house often, we played in the Mathers’ backyard as if it were our own. Beryl would have been in her mid-forties when I first knew her, but she played with us kids nearly every day. A single apple tree remained of the once-extensive orchard and a lone apricot tree. We picked their fruit, and climbed their branches. We climbed the maple and pinetrees in her backyard, and so did Beryl. She was eager to boost us onto branches higher than we really wanted to go. She never sent us too high, though, and she never left us sitting on a branch that we feared to retreat from. If we were too nervous to descend, she would climb above us and help us back down. My best friend Ellen who lived down the street was frequently at our house and played with us in Beryl’s yard. Ellen knew a game played with a softball and a bat that required only a few players. One of those players was often Beryl. We played in her side lawn and she gave us pointers, tossing the ball underhand so we could each have a turn at bat. Beryl let us pick the berries, grapes, and apples that grew out back and we treated her property as if it were our own. We missed Beryl and her mother when they moved away, but we enjoyed their yard for the next few years while the house stood empty. The berry bushes grew wild, unpruned season after season. We picked the currants and made jelly. In early July we ate the berries and in the fall gorged ourselves on the grapes. There were concord grapes, scuppernongs, and a little sweet red grape whose variety I never knew. The backyard next door, we believed, belonged to us as much as the yard behind our own house. That’s why we were so annoyed when the Hoppough family moved in and we were told by our parents to stay in our own yard. Bill and Bev had two little children, Darlene and Daryl. Soon there was a new baby, Darrin. Wendy and I, in our early teens by now, often babysat for the Hoppough children - of which there came to be two more: Kelly and Holly. Though the backyard was now off-limits, we were always welcome in Bev’s house. Inside there were many changes as Bill worked to update and remodel. The closed-in staircase was unwalled and the dark woodwork of the front room lightened up and the curtains drawn back. Bev told me that the wooden mantle had been fashioned and installed by Mr. Mather. The tiny kitchen at the rear of the house was expanded onto the back porch, windows were added and a new sink and oven installed. With its light-colored walls and opened-up space, what a pretty room it became! And just a bit more: I never knew Herman Heckman - I’m not that old - but in my research I learned that I had slender threads of connection to him. Loren Parsons, who was killed in 1904 when struck by Herman’s train, was my husband’s ancestor: the uncle of Alice Smith Lewis, my husband’s great-grandmother. And, weirdly, I also knew a little about Father Cluney, another victim of Heckman’s train. He was the priest at St. Joseph’s parish in Rush, and baptized my grandmother, Mercedes Farrell, in the spring of 1906.

|

||