Welcome to Hemlock and Canadice Lakes!

Barns Businesses Cemeteries Churches Clinton & Sullivan Columns Communities Documents Events Time Line Fairs & Festivals Farm & Garden Hiking Homesteads Lake Cottages Lake Scenes Landscapes Library News Articles Old Maps Old Roads & Bridges Organizations People Photo Gallery Podcasts Railroad Reservoir Schools State Forest Veterans Videos

|

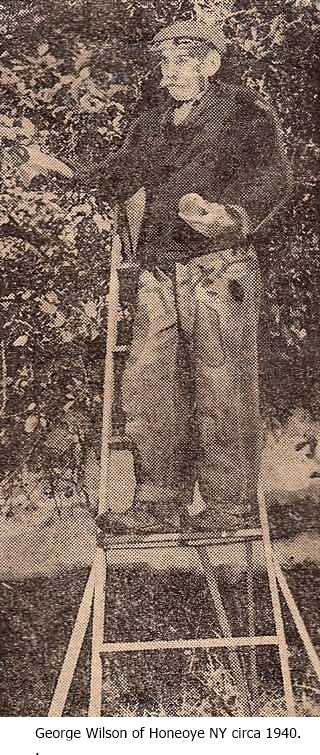

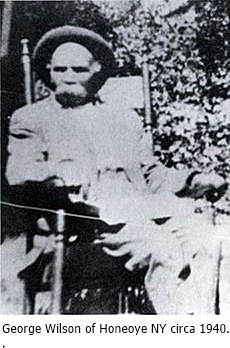

George Wilson |

|

|

George Wilson 1852 - 10 June 1947 By Peter Culross in 1941 |

|

1 “Hey, black boy! Wanna go for a ride?” Bill Moffet of Livonia looked down from his perch in the train window upon the little fuzzy-headed colored boy on the crowded station platform. All was tumult and excitement, this glorious morning in May 1865, for the war was finally over and Bill was going home. The nation’s capital was extending a final farewell to these, its conquering heroes. Amid the din of confusion and the babel of hurried farewells, two round eyes bulged with excitement and adventurousness. A ride in a real train! “Ah’ll sho’ have to git off at de fust stop,” the boy said. As the great iron horse bellowed, and then spit its way forward, and the crescendo of voices mounted into the soft spring air, it went practically unnoticed that a pair of chocolate-colored feet were swung up, and then devoured by the yawning mouth that was a railroad car window. At least one soldier in blue was to return with a “souvenir” of victory. Today, the still active 90-year-old Honeoye Lake farmer, George Wilson, chuckles as he recalls that “de fust stop”, which he intended to get off at turned out to be in Northern Pennsylvania, and the next at Livonia, N. Y. His eyes still moisten with the memory of the mother and three sisters he left behind. He has never seen them since that day he clambered aboard the train. Chewing on an apple, that he himself had just picked, this widely-known and respected old darky, with his whisk-broom mustache, admitted that his “schoolin” had taken him only as far as the fifth reader. One promptly perceives, however, that only a keen mind could account for the remarkable memory that is his. Born a slave, Wilson was one of four children who resided at the beautiful Struthers plantation overlooking the Rappahannock River (later the scene of the historic battle of Fredericksburg) in Fredericksburg, Va. “Covering quite a territory,” the plantation housed approximately 20 slaves, plus three overseers. Slaves were rationed so much food per week, according to their age and the size of their family. In a cookhouse, separate from the mansion itself, were prepared daily servings of corn meal for those in the fields or quarters. On special occasions, such as Christmas and Easter, wheat and flour were given as a treat. 2 While Wilson and his sisters, Margaret and Nancy, worked the fields, his mother and other sister, Sarah, served in the “great house with the white pillars” as housemaids for the Struthers, their three sons and nine daughters. “One Christmas Eve, when I was 3 or 4 years old,” Wilson recalls, “a man came to visit us. He was allowed to stay only for a few moments and so, after greeting us warmly, he kissed mother tenderly and left. Later they told me this man was my father. He had been sold to another plantation before I was 6 months old.” In the early fall of 1862, when George was approximately 10, President Lincoln appointed General Ambrose E. Burnside as commander of the Army of the Potomac. Burnside accepted the responsibility with great unwillingness, perhaps feeling unequal to the task. In any event, however, the whole Army of the Potomac was concentrated near the shores of the Rappahannock by the middle of November. It was Burnside’s plan to cross the river and push on to Richmond before Lee could bring his scattered forces together for an adequate defense. The Struther’s plantation, situated at this strategic point, served as a general headquarters for Burnside and his aides. The amazing nonagenarian (person whose age is in the 90’s) remembers “soldiers camped all over the place and the whole countryside in a tremendous turmoil.” “Mammy” Wilson, deciding that somewhere there must be a healthier spot to live gathered her children together amid the confusion of soldiers and gunfire, and headed for Washington. Although President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation was not yet two months old and was not officially to become law until January 1, 1863, thousands of colored folks, whose slavery background extended back generations, were converging from all points to the city of the Great Emancipator. For some unknown reason Mammy Wilson and her brood avoided the great new colored settlement on the outskirts of the capital, and found quarters on 10th Street where “we could look out the back window and see Ford’s Theater.” Some months later a smallpox epidemic broke out in the “settlement” and the little slave boy, now free, watched a new calamity befall his race. Hundreds of victims of the disease were buried. Two years later Wilson felt the impact of catastrophe. It was the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, friend of his people. “As I look back today I know now I didn’t fully realize what was taking place,” Wilson says. “When I rushed out into the street it seemed impossible that so many people and soldiers could have gathered together in one place in so short a time. People dashed madly in all directions, shouting that the President had been shot. I saw a woman bend down and touch her handkerchief to the pavement where a drop of the great Emancipator’s blood was said to have dripped as he was carried across the street to a boarding house. It was impossible to pass through the street. Many persons wept openly.” With Moffet, the slave arrived at Livonia June 1, 1865, and resided at the Moffet home until July 4th of the same year, when he moved to the Betsy Reed farm at Frost Hollow in the Reed district. While he was acquiring a somewhat belated education, George worked alternately at the Reed and Barkley homes and later at the Pennell farm in Honeoye. Now he lives on the east side of the lake about three miles south of Honeoye, on his own farm. In 1876 Wilson met and married Alice Rowe of Lima. The couple settled at Honeoye and became the parents of three girls and two boys. One girl, now Mrs. Georgia Bentley, employed at Madsen Hospital in Honeoye Falls, is the only other surviving member of the family. Today Wilson is alone. He is happy preparing his own meals and keeping his little home tidy. When each day is finished and the odd jobs about the farm are completed, he sits quietly with his tattered Bible and muses until sleep finally overtakes him. “Things were a whole lot different back when I first was married,” Wilson reflects. “There were Mamma and the children to take care of. Farming was a great deal more prosperous in those days and you worked hard from sun to sun. Then too, on the Sabbath, I had my Sunday School class to teach down at South Bristol. They are all gone now.” In nine decades the oldest farmer of the Honeoye Lake district has seen many changes in this country of ours. He believes that the younger generation is trying to “get something without work.” This, he concludes, is the reason for the migration of country youth to the cities. About his own future, Wilson hasn’t the slightest concern. “God has given me this land as a means of sustenance. I am ready to go when it is His will to take me.” Written by Peter Culross in 1941. |

||

|

Looking back Richmond George Wilson 1852 - 10 June 1947 |

|

3 “Hey, boy. Wanna take a ride?” called the Yankee soldier from his railroad car window to the 12 year old black youngster standing on the crowded Washington, D. C. station platform. It was June 1, 1865 and the Civil War had ended. Eager for the opportunity to ride on a real train, George Wilson climbed aboard and forever changed his life. Born to slave parents, December 1, 1852, on a plantation in Fredericksburg, Virginia, his father was sold to another plantation when he was only 6 months old. George saw him but once after that time. His mother and sister were servants in the plantation house. George and his other two sisters worked in the fields. Their daily diet consisted of corn meal, wheat, and flour on special occasions, such as Easter and Christmas. In the fall of 1862, the Army of the Potomac converged on the area of the plantation. To escape the scene of impending battle, Mrs. Wilson gathered her children and headed for Washington, D. C. She found lodging in a building on 10th St., whose back window looked out on the Ford Theater. In a newspaper interview in 1942, Mr. Wilson recalled the panic and turmoil after Lincoln was shot. “People dashed madly in all directions, shouting that the President had been shot. I saw a woman bend down and touch her handkerchief to the pavement where a drop of the Great emancipator’s blood was said to have dropped as he was carried across the street. Many people wept openly.” When George boarded the train at the invitation of Bill Moffett, a Union soldier from Livonia, he expected to get off at the next stop. That “next stop” was in northern Pennsylvania and the final, Livonia, New York. Alone and without money, George lived with the Moffetts for a month. Moving to Richmond New York, he worked for several farmers while acquiring a belated education at the district school in Richmond Mills. In 1876, Mr. Wilson married Alice Rowe of Lima. Eventually he purchased his own farm at 366R East Lake Road where his descendants still live today. An avid Bible reader, Sunday School teacher and friend to all, it is said he attended every funeral in the vicinity of Honeoye during his long lifetime. George Wilson, ex-slave, who became a highly regarded resident in Richmond, died in 1947 at the advanced age of 94 years. Postscript: Louise Sellers, granddaughter of Mr. Wilson, was interviewed in compiling this profile. She is since deceased, but one of her comments is worth mentioning. “Grandpa always raised sheep and had an apple and peach orchard down by the lake. If he could see it now, he’d turn over in his grave.” |

||

|

Death of George Wilson 1852 - 10 June 1947 Livonia Gazette |

|

George Wilson, a long-time resident of Honeoye, died at his farm home on the East Lake Road, June 10th, aged 94 years. Born as a slave, he came to Livonia when 12 years old and worked on several near-by farms and attended school. Later in life he purchased the farm where he lived until his death. He is survived by a daughter, Mrs. Georgia Bentley of Honeoye, three grandchildren and 17 great-grandchildren. Funeral services were held in Honeoye Congregational Church, Friday, at 2 pm, the Rev. Robert Gray officiating. Several hymns were softly played on the electric organ by the organist, Mrs. R. H. Francis. The floral offerings were many and beautiful. Interment was in Lake View cemetery. Mr. Wilson was highly esteemed by all who knew him and will be missed by his friends here. |

||