Welcome to Hemlock and Canadice Lakes!

Barns Businesses Cemeteries Churches Clinton & Sullivan Columns Communities Documents Events Time Line Fairs & Festivals Farm & Garden Hiking Homesteads Lake Cottages Lake Scenes Landscapes Library News Articles Old Maps Old Roads & Bridges Organizations People Photo Gallery Podcasts Railroad Reservoir Schools State Forest Veterans Videos

|

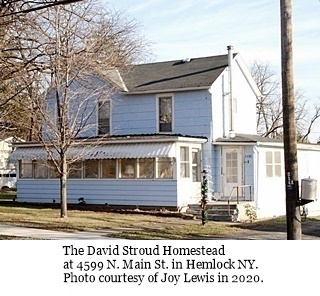

The David Stroud Homestead at 4599 N. Main St. Hemlock NY |

Click any image to enlarge. |

|

The Marble Factory - The David Stroud House at 4599 N. Main Street Hemlock NY

A Historical review by Joy Lewis, the Richmond NY Historian.

1 The David Stroud Homestead at 4599 N. Main St. in Hemlock NY. Photo courtesy of Douglas Morgan in 2007. The House is Built: 1848 Two brothers came to Hemlock from Canandaigua in the autumn of 1848 — David and Charles Stroud. David, the younger, was twenty-seven; he and his wife Mary were the parents of an infant son, Frank. For ninety dollars David bought the house lot on the northern boundary of the Stocking property. A few lots north (4581) his brother Charlie operated the cooper shop. David built a framed house on his half acre, four rooms up-and-down, with a shed serving as workshop behind. On the line between the Strouds’ lot and the Stockings’ lot to the south was a hand-dug well which the families shared. In the parlance of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, a “marble factory” indicated a stone worker who specialized in carving grave markers, whether of marble, granite, or slate. In the three years that David Stroud lived in Hemlock there were twelve individuals buried in the village cemetery on Clay Street, from three-year-old Frances Stillwell in the winter of 1849 to sixty-year-old Robert Morton some months later. It might be assumed that David was the maker of at least some of these headstones. When little Frank Stroud was three years old David and Mary sold their home and joined the flow of west-bound immigrants to Michigan. The Miller: 1851 Samuel Northrup, a long-time resident of Hemlock, bought the Stroud home, but he did not live there. For the four years that Mr. Northrup owned it, the house was rented to the family of John Haskell Gilbert. Thirty years old, Haskell was a husband and the father of an infant son, Randall. Orphaned before he was ten, Haskell was sent to Ohio to live with his Uncle Enos, then a few years later sent back east to Livonia to live with Uncle William, his father’s brother. William Gilbert, born March 7, 1798, in Vermont was one of the earliest pioneers to settle in Livonia, at the Center. The first miller in that area, he became a prominent and wealthy townsman. He and his wife Ursina raised three children, Lucia, Mary, and William, as well as nephew Haskell. In their early twenties Haskell and his cousin Lucia were married and a few years later “their union was blessed by the birth of a baby boy.” They named him Randall. Haskell was in the employ of Samuel Pitts who owned the grist and saw mills on the Hemlock outlet downtown. He’d learned the miller’s trade from his uncle and was a proficient and well-esteemed worker. In 1853 the mills changed hands when Marcus Hoppough became the owner. At that time Haskell and his family moved away from Hemlock, as Mr. Hoppough preferred to manage his mills himself. The Cooper: 1855 Samuel Northrup sold this house in April 1855. The new owner, George Glazier, took possession in the fall. Born in Michigan Territory eight years before it became a state, George was married there in his early twenties. His wife Jane gave birth to two children, Eliza and Martin, before she died in the tenth year of their marriage. A year or so later George brought the two children to New York where he settled in Castile in Wyoming County. There he met his second wife, Ann Gell. The two were married September 16, 1855, and within the month George and Ann, with his daughter and son, were living in Hemlock. George Glazier was a cooper. He conducted his business at the cooperage associated with Luther Lyon’s lumber yard, just a few steps up the street from his home — where Charles Stroud had worked some years earlier. Making a barrel was a time-consuming and meticulous job. First, the staves must be carved; these are the slats of oak that when assembled will create the barrel. Each stave is hand-shaped to be convex on the outside and concave on the inside, narrowed on the edges, and tapered at both ends. There are as many as thirty staves needed to make a barrel. The next step is to assemble the staves. An iron hoop is clamped to the top edge of the first stave, then a second stave is added beside the first, then another, each one fitted snugly against its neighbor and clamped at the top to the iron hoop. When all the staves are fitted into the top hoop, the cooper numbers them so that if something goes wrong in completing the work, the barrel can be reassembled without much effort. Another iron band is slipped over the top of the barrel and pounded into place below the top band. This begins the process of shaping the barrel. At this point the staves at the lower end flare out resembling a lady’s skirt. The cooper refers to this stage as “raising the skirt.” Next the unfinished barrel is soaked in water for several days, allowing the staves to become more pliable. Taken out of its bath and turned upside down, the other end of the barrel is secured with an iron band. Now comes the finishing touches as one or two more bands are added, and all the bands are tightened and secured. A disc of seasoned wood is permanently affixed to the bottom and another wooden disc is made to cover the top of the barrel. The lid, however, will not be affixed until the barrel is filled. Many hours of labor go into the creation of a single barrel. George had working with him, and living in his household, a young man named Pitt Fisher — the apprentice cooper. Within a few years his son Martin was old enough to be his helper. For nearly a decade the Glazier family lived in Hemlock. During those years three sons were born: George in 1857, Albert three years later, and Carlos three years after Albert. About eighteen months after Albert’s birth the family sold up and moved away, settling in Clayton County, Iowa, where two more Glazier children were born: Edward and Jeanette. The Wanderer: 1864 Recording the many moves of Ezekiel Wright over the course of his lifetime will wear down a pencil quickly. He was born in 1813 in Richmond, on the Wright homestead outside Honeoye. Over the course of his long lifetime he would live in more than twenty different houses. Ezekiel’s father Abijah was a colorful character in the early settlement of Ontario County. At age sixteen he had served in the Connecticut militia during the Revolution. After the war he married for the first time and three children were born to his wife Elizabeth. Betsey died, then Abijah married Roxanna Parker. They settled in Otsego County, New York where Roxanna gave birth to three children. In 1804 the Wright family came to Richmond. Their farm was on present-day Route 20A, near the intersection of Big Tree Road. Roxanna’s last child was born on the Richmond farm in a double-log house that Abijah built for his growing family. Roxie died in 1809 and in the spring of 1810 Abijah married for the third time. His third wife was Sally Parks, the mother of Ezekiel, and of three other children. Abijah was a devout Methodist preacher, faithful to his calling. Many stories have been handed down in the folklore of Richmond township concerning Elder Wright and his forthright character. In January 1812 he presided over the first religious revival held in Canadice. Scores were converted under his exhortation, and later that year Mrs. Pitts Walker, a woman of larger- than-usual dimensions, was to be baptized in the Canadice outlet. The water being quite shallow, Elder Wright, it was said, “turned her from side to side, so as to wet both sides.” With his three wives Abijah fathered eleven children; many settled in the mid-west, but Ezekiel chose to remain in western New York. He was not, however, “settled” as he worked as an itinerant farm hand, moving from farm to farm in Richmond and Springwater, before coming to Hemlock. While living here he continued to work as a day laborer for different farmers. After he moved away from Hemlock, he lived in a number of places in Genesee County. Ezekiel and Margaret (Stocker) Wright had been married for twenty-seven years when they came to live in Hemlock toward the end of the Civil War. Seven of their twelve children were grown by then, but still living at home were Alice, three; Rose, five; Lucy, eight; Charles, twelve; and Maggie, fourteen. Boarding with the family were an elderly couple, Jared and Mary Guerin. A few years after moving in to their new house, Mrs. Wright died and before the year was out their son Ezekiel also died; he was twenty-five. Before Alice turned ten, Ezekiel remarried. He and the new wife, Mary, moved a year or so later to Elba in Genesee County, leaving the house in Hemlock sitting empty for some years. A Decade of Tenancy: 1880 As the Rochester Waterworks Company continued to buy up land along the Canadice Outlet, families were forced out of their long-settled homes in Dixon Hollow. Many of these folks found their new abode in Hemlock. One such family was that of Richard and Susan Fox, who rented the Wright house for a while. Both were in their early forties; their daughter Katie was fourteen, their son James, nine. Mr. Fox, while living in Dixon Hollow had owned a drug store. When he came to Hemlock he clerked in the hardware store. Also living with the family was a young unmarried man named William Love, a tinsmith. The New Owner: 1889 Eliza Wright was the daughter of Ezekiel and Margaret; she was a “middle child.” Married to Clark Henry for a quarter century, she was the mother of seven children. The family had lived for many years in Richmond where Clark owned a farm. Sometime in the 1880s they upped stakes and resettled on a farm in Canadice. When she bought her father’s Hemlock house in 1889, she continued for several years to let it to renters, as did several of the subsequent owners. In the next twenty-five years the house changed owners four times: Eliza Henry to Lydia Reynolds, to Lydia’s son John Reynolds, to Matthew Norgate, and finally to Clarence Wemett. None of these owners lived in the house; each treated it as income property. Only a few of those tenants can be identified, as the Census records of 1890 were destroyed by fire some years ago. In 1900 the Hugh Patton family lived here. He and his wife Susan were both in their early forties, the parents of two sons and four daughters. Their baby, May, was less than a month old in early June when the census taker came by the house. After that, George Gladding and his wife Beatrice (Short) rented the house for some years. Married early in 1908, their daughter Pauline was born later that year. George was a barber, with a shop downtown. When the Gladdings moved out, the Covey family moved in. Railroad Engineer: 1919 A young boy, grandson of the new owner, grew up in this house. Jack Evans, when he was grown, wrote a detailed memoir of his family and his Hemlock boyhood called “Hemlock Memories.” In one piece he mentions that “near the end of World War I, Grandpa took the engineer’s position at Hemlock ... I was a few months old. My father was in the Army in Spartanburg, South Carolina. My mother and I came along with her parents.” It was early in 1919 that the Covey and Evans families moved into the house on Main Street, as tenants, and four years later that Jack’s grandfather, John Covey, bought the place. He paid one dollar down and arranged a $600 mortgage with Mr. Wemett, the former owner. Also living with John and his wife Emma were their unmarried son Ansel and their daughter Grace and her family — her husband John Evans and son Jack. Mr. Evans was employed by the “railway mail branch of the postal service” and was away from home for long stretches of time. Jack became particularly close to his grandfather, reveling in tales of ole-timey railroading. John Covey, born in the opening year of the Civil War, had grown up on a farm south of Buffalo. He was fascinated by the new-fangled railroad and determined to find his place in its organization. He began as a fireman on the Grand Trunk road between Niagara Falls and St. Thomas, Ontario, about 1880. Mid-decade he joined the construction crew of the Lehigh Valley Railroad, operating a steam shovel, digging the cuts of the the roadbed to be laid between Buffalo and New York City. “Where the mainline of the Lehigh crossed the Genesee,” his grandson wrote years later, “[John] unearthed various Indian relics, arrowheads and beads.” In his early twenties he was married to Emma VanSice, and in due time they became parents of three children: George, Ansel, and Grace. Emma, in her middle years, was injured in an automobile accident, shattering her kneecap. As a consequence she was lame for the rest of her life. By the end of John’s stint with the construction crew, he’d earned the job of engineer; he drove the great steam locomotives for more than forty years, first on the Buffalo/Sayre, Pennsylvania, run on the Lehigh mainline, then in 1919 as engineer on the Rochester run out of Hemlock. Jack remembered all his days his grandfather at work, dressed “in his two-piece blue denim overalls, wearing heavy leather gloves with large stiff black cuffs, and his striped denim cap with the long visor.” In the cab his left hand “grasped the throttle, his right arm rested on the windowsill of the cab, ready at any instant to reach for the air valve to apply the brakes.” Grandpa, it seems, was a lover of speed. Jack wrote of a particular trip, undertaken in the years John was running the mainline: “As No. 11 conquered the miles, Grandpa in the driver’s seat was as a king on his throne ... Between the Junction and Batavia, Grandpa reached for his pocket watch every few miles and observed the mile posts ... By his calculations, he was traveling between 65 and 91 miles per hour according to track conditions. Grandpa let up slightly passing through Batavia. Then came that absolutely straight level stretch of 40 miles into Buffalo. Grandpa hauled the throttle back to the last notch of its travel ... the speedometer needle crept upward to ninety, then ninety five, a hundred and ten, and levelled out at a hundred fifteen miles per hour.” The boy had a deep reverence for his grandfather’s locomotive, a respect shared by many passengers. At the end of every trip Engineer Covey would hurriedly disembark and commence faithfully to oil his engine. “Although he stood six feet in height he appeared tiny and obscure beside the locomotive. [Passengers as they passed by] always paused a moment to pay tribute to that behemoth of the rails, that magnificent iron horse ... They admired the massive elegance of it all, the coal black locomotive with its contrasting nickel-plated whistle, bell, cylinder heads, and hand rails — a decorated black monster on wheels.” It was the thrill of Jack’s young life whenever he was allowed to ride the rails with his Grandpa. Jack wrote extensively of his Hemlock boyhood. He had detailed memories of delivering the Times-Union newspaper at age eleven, attending the Little World’s Fair every autumn, feeding and milking Dr. Trott’s cow which was kept in the Coveys’ barn in exchange for some of the milk. He and his friend Bruce Wemett once climbed the abandoned water tower on Railroad Avenue, which was full of pigeons and danger. They fashioned a homemade rowboat and took her sailing on the mill pond. “One drizzly Saturday in April I caught seventeen catfish in that tub while floating beneath the umbrella,” he remembered. He and his friends swam in the creek on Adams Road, jumping off the railroad trestle into the murky water below. With Bruce and other boys he “ice skated [on the mill pond] in winter, boated and fished in summer.” The dam which formed the pond provided a canny boy with “a clandestine route into the fairgrounds, thereby avoiding paying the admission charge.” Vividly Jack remembered the first barnstormer to fly into Hemlock Airport in his WWI biplane, a Jenny. The year was 1929 and Jack was ten years old. Children and adults alike flocked up the hill to see the plane, a two-seater with an open cockpit, a wooden fabric-covered frame painted with a colorful American flag, a six cylinder engine, and a two-blade propeller. The sight of that plane and the daring pilot outfitted in his “brown leather flight jacket and leather helmet with goggles” was one Jack never forgot. 1930 brought deep sorrow to the Covey and Evans families. Jack was twelve years old in the fall of that year when his beloved Grandfather Covey died after a four-day siege of “intestinal grippe.” His obituary gave the details of his life and family, but it is Jack’s eulogy that bears witness to his grandfather’s lifework: “The period in which Grandpa grew and prospered corresponded with the crescendo of the American railroads. The railroad did not offer me the lifelong opportunity that it did to Grandpa, but the railroad, with its many attendant experiences, did offer me an exciting, enlightening and happy beginning. I learned many things from the railroad — about machines and personalities and their meshing together, about attention to duty and punctuality. I reveled in the pastimes it provided — walking the track, riding the rails, diving off the trestle, fishing in the pond and exploring the railroad property. Ah! The railroad, what memories ... ” Less than two weeks after Mr. Covey died the family endured another blow when on September 23, his widow succumbed to pneumonia. Jack’s Uncle George, his mother’s brother, died later that same day. Not surprisingly, Jack wrote little of this heartbreaking time. He and his parents continued to live in the house and his mother rented “the room and bath right off the kitchen that Grandpa and Grandma had occupied” to Mr. Jacob York Baker, the new engineer who was stationed in Hemlock. Mr. Baker’s family, a wife and three daughters, remained in Manchester; he returned to visit them nearly every weekend, sometimes taking Jack along. Jack graduated from Hemlock High School, valedictorian of the class of 1935. He and his parents moved to Rochester that summer and for the next several years this house was rented. An Interval: 1936 After the Evans family moved to Rochester, George Owens, a teacher at Livonia Central School, lived here with his wife Anna, his grown daughter Ethel, and Anna’s brother Frank Kelly. A few years after the Owens family moved out, Clayton Harvey and his family moved in; he and his wife Ethel (Stevens), both in their early forties, had three children: Dorothy, nineteen; Robert, fourteen; and Richard, eleven. In the summer of 1943 when the house was sold, the transfer of deed specified that the Harvey family be allowed to finish their rental term. A few years later the house again changed owners. A New Owner: 1948 Mr. Clifford Peck bought the house in 1948. He was the husband of Pauline (Flood) and the father of two daughters: Betty was nineteen and Clarice was thirteen. For more than a decade the Peck family resided here.

|

||